アリ地獄天国 「Ari Jigoku Tengoku」

Release Date: June 06th, 2019 (USA)

Duration: 98 mins.

Director: Tokachi Tsuchiya

Writer: Motoharu Iida, Tokachi Tsuchiya (Script)

Starring:Yu Nishimura, Tokachi Tsuchiya, Naoko Shimizu, Kotaro Kano (Narration)

In 2017, the Japanese word karoshi, death from overwork, entered the global lexicon when news organisations covered the case of advertising firm Dentsu which was fined by a Tokyo court for violation of labour laws following the suicide of an overworked employee named Matsuri Takahashi who had been clocking up 100 hours a month in overtime prior to her death. Her story came out around the same time as the one of NHK journalist Miwa Sado who died two years earlier after she logged 159 hours of overtime in a month. Analysts, public health experts and cultural commentators published articles stating that they are just the tip of the iceberg.

Although karoshi is a term that has been around since the 70s, the unhealthy work culture that results in depression, suicides or strokes amongst workers has been identified as being linked to the post-war economic miracle when employees were asked to dedicate their lives to their jobs. However, in the 90s after the economic bubble burst, things worsened as worker protections were sacrificed on the altar of free market capitalism and people were chewed up by their employers. In response to this, and a falling birth rate, the government has introduced measures to give employees more time off work. Things have yet to get better.

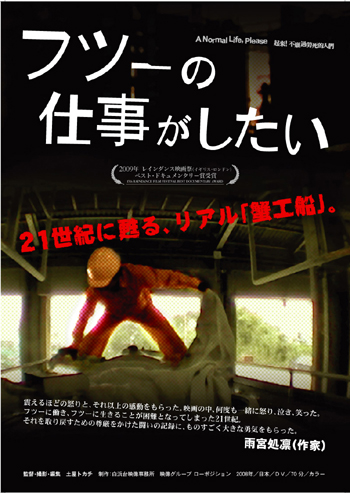

One filmmaker who has been tracking stories of everyday people being sacrificed for the economy is Tokachi Tsuchiya who started out as a freelance videographer and became a documentary filmmaker with his award-winning debut A Normal Life, Please! (2009) where he exposed the exploitation of workers through an average truck driver named Nobukazu Kaikura who was made to work by his company “552 hours a month without benefits or sick pay, a regime that barely affords him time to wash or eat” (source). The film covered Kaikura’s decision to join a worker’s union and the unsavoury characters hired by his company who tried to crush the workers who were simply defending their rights.

Since then, Tokachi has worked for an NPO making films about capitalist exploitation and state oppression while also doing “making-of” videos for Momoko Ando’s 0.5mm and Gen Takahashi’s Court of Zeus. With An Ant Strikes Back, he is back with a story of a worker who fought for years for better treatment at his job after horrendous exploitation and mistreatment and it is a shocking eye-opening insight into unfair labour practices in Japan and how unions protect workers.

An Ant Strikes Back starts with a prologue that introduces some sobering facts about karoshi before introducing the director to viewers and here he relates how his friend “Yama-chan” was a victim a number of years before. We understand that his perspective will be a factor in understanding karoshi. Then we are introduced to the worker “ant” at the heart of the film, Yu Nishimura.

He was an employee of Busy Ant Moving Company after joining in 2011 because he was seeking a stable salary as he was about to get married. At first, everything was fine. He was a full-timer who quickly rose through the ranks thanks to his dedication and he soon made it to the sales department and managerial roles where he became the top performer but, we learn that his performance, which included 19 hour workdays and 392 hours of overtime a month, wasn’t rewarded financially. What about loyalty from his superiors? Forget that.

Despite being a loyal worker, an accident caused by fatigue from overwork meant Nishimura triggered a clause in his contract whereby he would have to pay compensation. In an attempt to challenge such an unfair rule, he joined the Precariat Union which protects workers but his efforts at defending his rights were punished by the company through constant workplace harassment and humiliation from his bosses. They reduced his salary, subjected him to unfair dismissal, racist abuse, and public defamation. This led to physical and mental suffering on the side of Nishimura who wanted nothing more than to just work at the company.

Tokachi entered midway through this ordeal with filming starting in 2013/4 and lasting for three years. He first encountered Nishimura when he recorded a press conference given by the union and, deciding not to stand by and let another person get crushed, took part in recording events. Thus the present-tense narrative and past merge as Tokachi is able to link back to his friend Yama-chan. This gives the film a sense of the extent of karoshi and workplace exploitation and its devastating social ramifications for those suffering it and those left behind.

To fully illustrate the problems, Tokachi created a documentary that lays out all of the facts in Nishimura’s case to present a fully detailed picture of how a toxic work culture works. He uses Nishimura’s explanation, a narrator, on-screen text, shots of contracts, newspaper clippings with second-hand information and direct-to-camera interviews with people involved with the company and union who provide first-hand testimonies. His recordings also capture the belligerent bosses whose bullying behaviour which will do much to turn viewers against them.

The picture all of the evidence paints of Nishimura’s employer is one of low labour standards, systemic racism, and intimidation tactics that are used against many people. While against the law, lax attitudes from authorities and a culture of conformity and complicity, which Nishimura admits he took part in, enabled the bully bosses to exploit their workers and gouge them for massive amounts of time and money. And yet Nishimura insisted on staying with them. Why?

Like a good worker ant, he wanted to play his role. His hardworking nature was exploited. When it was revealed the extent of his exploitation, the sheer unfairness of the situation for himself and others prompted him to take a stand.

Nishimura isn’t so much a charismatic hero, quiet as he is, but his diligence and earnestness are his powers. These are qualities not as valued by films but brought out here as the camera watches him carefully. We see his vulnerability appear at high stress moments as well as his remarkable tenacity. Viewers will marvel over how he sticks out the abuse he suffers, some of which is recorded on cameras and microphones as the bosses yell at him and his union supporters. The few times when he lets his emotions out are captured in verite power, especially the sequence where Tokachi steps in front of the camera to join Nishimura in in a union meeting and tearfully makes the links with Yama-chan and Nishimura’s case.

With the brutal world of work exposed, the battle is long and arduous but the viewer is always kept on top of facts and it never feels dull. Indeed, it feels important and moving Tokachi’s film presents a personal story and a general truth about society and how exploitation occurs and the term karoshi has come to exist. As depressing as that sounds, seeing the gutsiness and camaraderie of the union with members like the alternately stoic and feisty Naoko Shimizu and some perceptive union lawyers who methodically build a case, we are reassured that there is hope out there as people work together and collectivise to protect everyone’s rights. It ends on a note of hope as Nishimura regains a sense of himself, his honest and hardworking nature overcoming a more powerful foe, like an ant striking back.

This film is playing as part of Nippon Connection 2020 and is available to view across the world.